by Oscar O’Sullivan

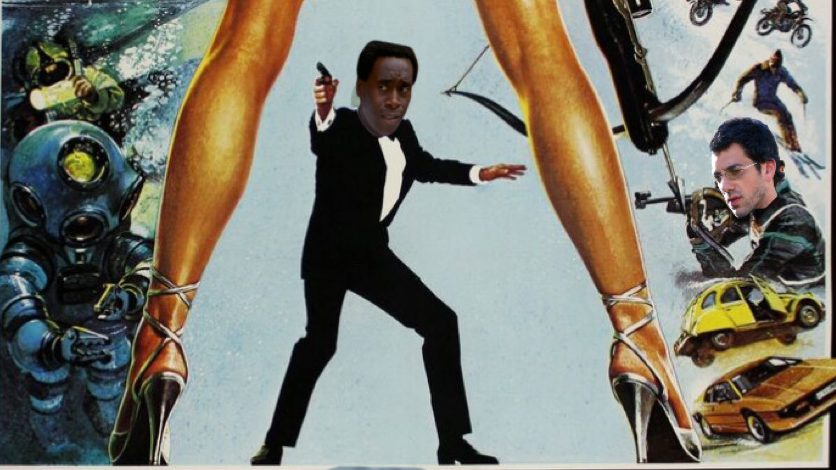

Monday – For Your Eyes Only

Much as I love the elevated tone and casual irreverence of most of the Bond films so far, watching one suddenly take itself completely seriously was a real eye-opener, especially right after the series reached the absolute pinnacle of camp fun with Moonraker. For Your Eyes Only takes a complete opposite tack, though the opening may be a confusing tonal swerve at first. The events of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service are once again called back to, with Moore’s Bond visiting the grave of the wife Lazenby’s Bond lost. It’s interesting that this detail has become the defining piece of backstory continuity for Bond when the film it hails from is in many ways the black sheep of the series. Bond’s mourning is interrupted by a conveniently faceless Blofeld, back from a long rights-based absence, leading to a frankly laughable action setpiece with a remote-controlled helicopter and Blofeld reduced to a bit-part gag villain unceremoniously dumped to his death. It’s a rotten way to start the film, but winds up working, in hindsight, as a sort of mission statement – after multiple entries of increasingly campy throwbacks, Bond is finally dumping that silliness and moving forward. The scenes that open the movie proper make this new tone more apparent – a grim sequence of sailors dying in a sunk submarine and our female lead Melina (Carole Bouquet) watching her parents violently gunned down in front of her eyes. Melina represents one of the film’s most successful innovations – making the Bond Girl a full character. While previous love interests were sometimes given their own competing vendettas, most were immediately supplanted by their selfless love for Bond, becoming little more than objects of titillation and to be saved by our hero in the climax. While the sparks do quickly fly with Bond, their romance isn’t consummated until the very end of the film, allowing Melina to retain her own agency as she pursues revenge against her parents’ killers. Moore has also got Bond’s characterisation back on track after the last two entries made him cartoonishly flippant. Moore’s Bond is a proper professional who takes his work and the safety of others very seriously – though he’s not above enjoying himself in the line of duty, of course. Most tellingly, Bond actually turns down casual sex with a bubbly, barely-legal blonde, showing a level of maturity and good sense that would have been unthinkable in previous films. The stakes of the plot have been reigned in from the apocalyptic doomsday schemes of the last two outings, instead concerning a small-scale intrigue with a drug cartel and a stolen intelligence system being auctioned off to the commies. It even manages to have an effective and understated twist villain, a welcome change of pace after previous megalomaniac baddies became impossible to take seriously. Above all, there’s an unmistakable sense of finally taking a definitive step forwards. While the escalating budgets of Moore’s outings have seen the action ramping up in quality, the general presentation and filmmaking technique has remained firmly rooted in the series’ 1960s roots, giving the last few entries an unavoidable B-Movie quality. The first Bond movie of the 80s finally feels like a product of its time, in large part thanks to the sleek, modern way the action has been shot. The standout set-piece is the extended ski-slope showdown, stunningly shot on location with a mobile camera that puts you right in the thick things and very little of the corny rear-projection effects that often break up the action in these sequences. The finale is also a wonderfully straightforward and small-scale set-up, with Moore scaling a dizzying cliff-face and assembling a small team of allies to quietly and efficiently take out a compound full of baddies. Though I enjoyed the OTT histrionics of prior films, this is a much-needed change of pace. Here’s hoping Moore’s last two outings stick to this more serious tone (though I somehow doubt a film titled Octopussy will deliver compelling, adult drama). 8/10.

Tuesday – Spartacus

The first and last time that Stanley Kubrick worked as a director-for-hire, Spartacus is nevertheless a dazzling, stirring beast of an epic. Very little about the story or presentation screams Kubrick, being far more sentimental and heroic than anything else in his filmography, but the images are still masterfully constructed – far from phoning it in, Kubrick clearly took advantage of the budget on offer to practice large-scale filmmaking. Kirk Douglas commands our attention as Spartacus, the slave who leads a revolt that brings Rome to its knees. He is everything a hero should be, kind, brave and generous, the tragedy of his origins lending him even greater nobility. Even as he becomes a legendary figure to the slaves he frees, the film makes sure to continue presenting him as comfortingly human. He laughs and jokes, he loves, he cries. A great strength of the script is how it populates the ancient world not with stock archetypes but with real, complicated human beings. The villainous Crassus (Laurence Olivier) is a wealthy bigot, but he is also disarmingly affable and a genuine man of his word. Despite his desire to restore dictatorship to Rome with himself as the unopposed ruler, he insists on operating within the confines of democracy, refusing to sully his eventual victory by harming the nation he loves in any way. Other characters reveal hidden depths as the story progresses – for example, fellow slave Draba (Woody Strode) is introduced as cold-hearted operator who refuses to befriend men he may one day have to kill. But, when his conviction is put to the test in a duel to the death for the entertainment of wealthy visitors, he unexpectedly spares his opponent and valiantly dies in an effort to strike back against the real enemy. The visual beauty and rousing action sequences may grab our attention, but the wonderfully three-dimensional characters are what keep us invested in a film that feels much shorter than its three-hour-plus runtime. 9/10.

Wednesday – The People’s Picturehouse

Great lineup this month. If you’re not attending Cork’s monthly short film showcase, I don’t even know what to say to you.

Friday – The Man from Laramie

A western with surprising emotional complexity, The Man from Laramie combines the classic images and tropes of the genre with a gripping social drama where appearances are often deceiving. In fact, to seriously dig into the plot would likely rob the twists and turns of their deserved impact. In brief, James Stewart plays the title character, who drifts into the frontier town of Coronado and quickly winds up in trouble with a local cattle baron and his hot-heated son. While the baron (Donald Crisp) proves to be thankfully level-headed about the whole affair, his difficulties with his idiot son (Alex Nicol) and overlooked right-hand man (Arthur Kennedy) threaten to escalate into outright chaos. Stewart, meanwhile, has his own secretive reasons for sticking around, involving apache raiders, smuggled guns and, of course, revenge. Stewart is superb in a role that seems at first to fall a little outside of his usual wheelhouse of loveable everymen. His natural charm makes it easy for us to immediately root for him, even when he starts throwing insults and punches with reckless abandon. His usual affability also makes his moments of icy intimidation and seething rage all the more effective. The audience is left constantly in the dark about character’s true motivations – some reveal a long-buried sweetness, while others harbour dark impulses. A twisty and complicated thriller dressed up in the skin of a dumb fun cowboy actioner. 9/10.

Saturday – Snowpiercer

It’s been said before but I’ll say it again – Chris Evans has wasted his talent. And I don’t mean wasting his time in superhero movies either, as his Captain America was one of the best leading-man performances in the franchise. It seems that since 2019, when he appeared in both Endgame and Knives Out to critical acclaim, he has simply had no interest in doing any sort of real acting, appearing exclusively in disposable streaming excrement, phoned-in voice roles and self-referential cameo parts. Watching his turn in Snowpiercer, you realise how much of a waste that really is. Evans is fantastic as the beaten-down hero of this dystopian narrative, a born leader whose deep self-hatred prevents him from fully stepping up to the plate. When we finally learn why he reproaches himself so, it’s the film’s darkest and most moving moment, sold entirely through the expression on Evans’ face and the pain in his voice. The overt absurdity of the premise and environment belies a blunt thematic simplicity that comes through in unexpected moments. Nowhere is this more apparent than during the last act, where Evans comes face to face with the master of the train, Mister Wilford. Ed Harris plays the character not as a cackling megalomaniac but as a chillingly mundane presence. The man behind the decadent, soul-crushing insanity of the eternal engine is simply a results-obsessed pragmatist. Even worse, he’s ultimately correct – the train is the last remnant of humanity, and the only way to keep humanity alive in a frozen world is to enact his brutal system of checks and balances. This is why the film feels like such an essential work of dystopian fiction – it understands that these stories are often even more effective without an element of hope. The only serious flaws of the film are a tendency to over-explain itself in places where it would be as well off staying quiet, and the sometimes distracting sloppiness of the action, which quickly descends into indistinct muddle while gesturing at some promising ideas. These are ultimately minor quibbles in the face of the incredible story, fascinating world design and fully-stacked cast of stellar performances. 9/10.

Leave a comment