by Oscar O’Sullivan

Monday – Diamonds Are Forever

Lazenby gave it his best shot, but damn if it isn’t good to take one last ride with Connery. Less human but far more entertaining to follow, the unflappable professional whose borderline psychopathy becomes a part of the charm. There is a semi-serious attempt to establish continuity with On Her Majesty’s Secret Service – opening with an intense Bond on the warpath against Blofeld – but as always, these films are designed to stand alone, so a change of face is never jarring. Is it coincidence that doubles and duos play such a major role in the follow-up to Bond’s first re-cast? Many twists and turns in the plot revolve around fakery and duplicates – Blofeld protects himself with identical body doubles and stolen identities, priceless diamonds are swapped for worthless imitations, and Bond twice assumes false identities to avoid detection. He also woos two women (with the more improbably named one being murdered in the place of the other), tangles with two eerie and congenial hitmen, and even roughhouses with two high-kicking Amazons, who get in some good licks before their inevitable humiliation in Bond’s capable, masculine hands. We’re back in familiar territory, as Bond jets around the globe to take down a Blofeld who is even more of a comic book villain than ever before. It’s silly, improbable, certainly misogynistic in ways I can’t even begin to comprehend – but God help me, I had fun. Whatever faults the script may have, the dialogue isn’t one of them, and director Guy Hamilton defined this mode of heightened spy action in his previous effort, Goldfinger. That connection explains the silliness that infects this outing – Goldfinger was the first entry to embrace the cartoon camp of the premise – but it does still feel a little disappointing after the Lazenby effort, for all its faults, proved that there was an emotional depth under the surface of Bond just begging to be dragged up and utilised. That drama would have been out of place in this straightforwardly entertaining entry, which delivers the goods in its own way with a smile and a wink. 9/10.

Tuesday – Elf and Tangerine

A deceptively simple film that has nevertheless become the last widely accepted holiday classic, Elf is a relentlessly charming experience, managing to be moving even in spite of how blatant its manipulations are. As is often the case, the score does the heavy lifting, full of soaring melodies so tried-and-true that the sound alone will move you regardless of what is actually happening on screen. Favreau’s filmmaking is solid and dependable, favouring practical fancies and occasional winking flourishes, like the Ringwraith-inspired presentation of the Mounted Police in the climax. And of course, the cast keeps everything running smoothly – Ferrel’s balancing act of annoying earnestness is just right, making a character that irritates on paper into somebody we genuinely like, while James Caan plays things perfectly straight as his distant, easily-riled father. But I don’t need to tell you this – odds are good you’ve seen Elf at least once. For all it’s hoke and predictable sappiness, it’s impossible to be mad about a film being so straightforward in its tackling of the holiday, especially in the face of the modern Christmas film landscape, where your choices are TV movies or cynical blockbusters where Santa has been pumped full of steroids to fight evil snowmen. None of that to be found here – just good, clean festive fun for the whole family. 8/10.

A film that fundamentally annoyed me, though not to the level is disliking it. Tangerine is a loose collection of scenarios, certainly not plotless, but not concerned (outwardly) with questions of form or structure. It’s a glimpse into a sub-culture, warts and all, as we follow a day in the life of a transgender ex-con looking to hunt down her pimp’s new girlfriend. Nobody in the film is admirable, or even likeable, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have empathy for their situations. Shooting on phones adds to the constructed realism of the story. It’s not shot in a documentary mode, but it does slip into a neutral fly-on-the-wall perspective in-between the overtly emotional outbursts. The score is a mixed bag, alternating between glaringly obvious classical mood music and seemingly random bursts of aggressive modern beats. At worst, it’s fascinating. It develops an emotional backbone as it progresses, though that almost seems besides the point, if not in outright opposition to it. This is a window into a world most of us will never be a part of, and we’ll all draw our own personal conclusions from what we see. To try and guide our eye is perhaps inevitable, an inherent limitation of the narrative form, just one that the filmmakers could have maybe tried a little harder to fully shuck. 7/10.

Wednesday – The Last of the Mohicans

During an exchange between British officers early in The Last of the Mohicans, one remarks that British foreign policy boils down to the maxim “make the world England”. This sums up the central thematic conflict of Mann’s period epic, where ordinary folks trying to scratch out a life of freedom in the New World are dragged kicking and screaming into the conflicts they thought they had left behind in the old one. And as always, calling America the New World is completely erroneous, because the Native tribes have been there since time immemorial. The two tribes we learn most about through the film are the titular Mohicans and the Huron, the tribe of the film’s villain Magua (Wes Studi). While it isn’t the primary focus of the film, the approach these two tribes have taken to integrating with the settlers is illuminating and adds depth to the story on rewatch. The Mohicans, reduced to only two living members, are nevertheless on good terms with the white man – they are friends with the frontier settlers, willing to co-operate with British soldiers, and even raised a white child as one of their own. In many ways, they seem to be above the conflict of order versus freedom, living by their own leave without having to stoop to the level of their enemies. But they are still subject to the changes sweeping the continent, forced to fight for their survival as they are caught in the conflicts of others. The Huron, and Magua specifically, are more active in their efforts to meet the changing world head on. They fight for the French to secure their own position, with Magua plotting to grow the tribe’s power and subjugate other nearby groups. Rather than try to preserve their old ways, Magua and the Huron have responded to the destruction wrought by the colonial powers by becoming like a colonial power themselves. Pay evil unto evil, the good book says. And Magua understands evil – but was that evil something he learned, or something within him all along? By that same token, Hawkeye (Daniel Day-Lewis) has the strongest moral backbone of anyone in the film, largely because he ignores the customs and expectations of the colonial powers. His raw humanity, his honesty and generosity, become reasons for the British to punish him – his good qualities are so self-evident that seeing him imprisoned for them makes others question the entire system of British judgement. Michael Mann’s films usually deal with advances in technology and rigid societal structures altering the way people relate to the world and each other, mainly through the lens of crime and punishment. Here we see a world on the cusp of being, the last free places falling under the shadow of colonialism, those who are driven to fight for their survival already being labelled criminals and villains by the systems that drove them there in the first place. Thus begins a timeline of ‘advancements’ that ends with Mann’s Blackhat, where the natural world may as well no longer exist as the digital realm subsumes every aspect of life. But the spirit of Hawkeye persists through the three core tenets that see Mann’s heroes through – love, independence and incredible violence. 10/10.

Thursday – The Age of Innocence

A rare page-to-screen adaptation that loses almost none of the interiority or attention to detail that makes the book so rich. While the prosaic voiceover may seem blindingly obvious, it functions as a sort of commentary track, a neutral observer guiding your attention towards the unspoken rules of New York high society and the subtle, subconscious decision-making of the central characters. Far from simplifying the emotions and story of the film, the effect of this guiding hand only enhances and highlights the subtlety of the performances – if you look closely enough, you can see Daniel Day-Lewis and Michelle Pfeiffer are playing every tiny detail of internality that the narration suggests. On a wider scale, the way specific details are captured through attentive editing and sharp cut-ins adds even more depth and texture to every image in this stunning period piece. And of course, the most important things are left unsaid. This is a story about the impossibility of connection in a world so strictly governed by invisible rules that you couldn’t see a way out even if you wanted with all your heart to leave. Love, Scorsese tells us, is not enough. Maybe Newland would have been better off if he’d never loved at all. 10/10.

Friday – Phantom Thread

Rounding out this unofficial trilogy of ‘Daniel Day-Lewis discovers the power of love in a period piece’ films, we have Phantom Thread, his final film role (for now) and probably the greatest character he ever played, Reynolds Woodcock. Reynolds is a supremely difficult man, a genius tailor and unbearable fusspot who throws away relationships over trivial irritations and lives his life by a bizarrely rigid schedule. He’s not without his good points, successfully wooing Alma (Vicky Krieps) and inviting her fully into his life, but he almost seems to self-sabotage as they become closer, using his work and his manias as an excuse to push her away, almost daring her to leave him so he can start the cycle all over. But in Alma he has met his match – she is every bit as stubborn as he is, strong-willed and persistent. She challenges him and his routines in a way that drives him up the wall, but when he needs comfort and to come down from his highs of genius, he can’t be without her. By any measure, this is a toxic relationship – and that’s what’s so beautiful about it. How many love stories have we seen where a moody, difficult or even outright awful man treats a wonderful woman like shit until, as if by magic, her patience and kindness redeems him and all is well? This is not a woman fixing a man, this is a woman making herself worse to match his crazy to an almost dangerous extreme. But through all the fights and tensions and creeping dread that it’s not worth the hassle, there is still beauty and warmth at every turn. Love conquers all – it doesn’t make everything better, but it makes the bad parts worthwhile. 10/10.

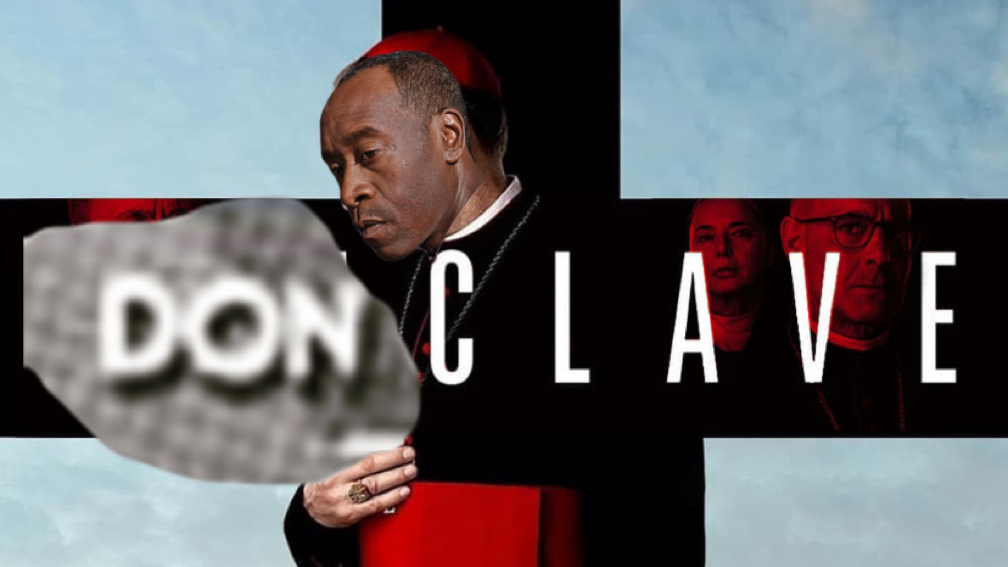

Saturday – Conclave

What is this really saying about the Catholic Church and modern religion? Not every film needs to carry a moral message or societal commentary, but there are some premises that naturally carry an obligation to make some sort of point. Much is made of the duelling ideologies of the parties assembled to choose the new Pope – a hardcore conservative block of religious traditionalists faces off against scattered liberal factions in a conflict that becomes increasingly nasty and personal. However, little is resolved or unearthed in the way events unfold. Cardinal Lawrence (Ralph Fiennes), recently suffering from a crisis of faith, is forced to wrestle with ethical decisions over revealing damning information about his fellow cardinals, as well as face the terrifying possibility of becoming Pope himself. Yet the film ends with his issues unresolved and unexamined, outside forces taking most of the tough decisions out his hands. Every character seems to have their one moment of relevance, an explanation of their motives and what they aim to achieve, before they are one by one disarmed and shoved aside in a manner that is almost too convenient and linear. For a film that sells itself on political intrigue, there are very few genuine surprises. There’s also scant few visual surprises – the film has strong compositions and occasional flourishes of expressiveness, but also suffers from so-so lighting and a repetitive conventionality in the way it frames dialogue, barring some eye-catching group scenes. Despite not being as gripping as you’d want this premise to be, it remains entertaining, with the stellar cast doing the heavy lifting – even if what they’re saying isn’t amazing, the way they’re saying it will keep you hanging on to every word. A solid drama with an absurd ending, though not really as campy as online reactions would have you believe. 7/10.

Sunday – The Keep

Michael Mann’s most mysterious film, a fantastical horror that he’s essentially disowned due to studio interference, rarely in circulation but with a strong cult following. I’m not sure what to make of it as a story – since over two hours of this film were cut out by the studio, it’s impossible to know what the full picture was meant to look like. Everything is exceedingly rushed and compressed, relationships and motivations shifting on a dime, when they’re even revealed at all. Some scenes that illuminate the wider themes survived, but those moments of explanation only serve to make what remains seem even more directionless. And yet, through pure elemental energy, the film remains compelling. Even on the battered, compressed, VHS quality version streaming on Paramount Plus right now, you can tell how gorgeous the film is supposed to be. Scenic village vistas, the oppressive atmosphere of the titular keep, dreamlike mindscapes of shifting smoke and lights and Mann’s signature high-fidelity close-ups. This is a difficult film to rate because I know I’m not seeing the full picture – it’s as if all we could see of the Mona Lisa was a close-up of her hands. What I know is that I like what I see. Need to watch it again in high definition. 8/10.

Leave a comment