by Oscar O’Sullivan

Monday – Inland Empire

Plotless by its very nature, Inland Empire began life as a series of digital camera tests that Lynch enjoyed so much he decided to string them together into a feature film. Ostensibly a story about an actress whose sense of reality begins to drift as she films a ‘cursed’ script, the film very quickly abandons tangible logic to throw the audience directly into the psychological turmoil that its characters are experiencing. The handheld cinematography and use of extreme angles creates an uncomfortably voyeuristic feeling, as if these are images that you were never supposed to see – women trapped in hotel rooms, murder on the streets of LA, sordid on-set affairs and more are shown in such close detail that you feel a part of the story. Laura Dern does phenomenal work creating a performance that works without any context to ground it, playing a character whose circumstances are constantly shifting as the world around her warps in completely unpredictable ways. There aren’t enough words to go into everything that happens in this film or to even begin to discern the meanings behind the imagery, so I’ll leave you with this – the film’s credits roll over assorted cast members and a monkey having a dance party. 10/10.

Tuesday – Drag Me to Hell and Crimson Peak

Sam Raimi’s Drag Me to Hell is mean, mean, mean. All of his movies are, to one extent or another – Evil Dead torturing hapless teens for laughs, The Quick and the Dead gleefully gunning down unlucky cowboys, even his Spider-Man films regularly presenting comedy at the expense of poor Peter Parker. What sets this film apart in nastiness is how relentlessly cruel it is to a character who, by any measure, does not deserve what’s coming to her. One mistake sets Christine’s life tumbling down into a never-ending string of horrible punishments, with her attempts to break free of the curse arguably digging her even deeper. It seems at first to be a film that wants to impart a lesson upon Christine, teaching her that there are more important things in life than her career and that she shouldn’t let ambition change who she is. And she does learn that lesson – and it doesn’t matter. The forces of evil aren’t interested in apologies, redemption or anything of the sort. They are interested in creating kinetic scares and awful social situations, often at the same time – see Christine gushing blood from her nose like a firehose all over her boss, or stumbling unexpectedly into a funeral and upending the table the guest of honour is resting on. Raimi is the king of the ‘fun scare’, executing violent and disgusting moments with such over-the-top audacity that you’ll almost be rooting for the demons. While I understand some being turned off by how undeserving the victims are, I think it adds a level of pathos that is often missing from horror films where bad people get their comeuppance. Christine is a fundamentally good person who makes some mistakes, her relationship with her boyfriend is sweet and well-rendered, and I think all this gives a welcome emotional weight to events as her life is consumed by demonic trickery. Not for the faint of heart. 9/10.

In Crimson Peak, protagonist Edith is struggling to get her book published because it is dismissed by those who read it as a ‘ghost story’, despite Edith’s insistence that the ghost is merely a metaphor. In the same way, Guillermo Del Toro presents to us a dark love story that happens to feature ghosts – not a ghost story, as the marketing and visuals surrounding the film would have you believe, but a story where there happens to be ghosts. By this stage of his career, Del Toro’s reputation was well-established as a purveyor of dark fantasy and action blockbusters. If this was an attempt to break free of that label and expand his horizons, I wouldn’t say it was an especially successful one. The supernatural element and gothic visual design very much overpowers and obscures the core story, a tragic romance that never has enough breathing room to become entirely gripping. While the film is mostly well-acted across the board, that’s not enough to imbue this story with the emotionality is really needed to reach its full potential. Del Toro keeps us at too much of a distance, treating the film like a beautiful but fragile diorama – look, but don’t touch, he seems to say. It is undeniably gorgeous, Del Toro’s visual blend of classical talent and mastery of modern technique on full display, but man cannot live on aesthetics alone. For a Del Toro film that successfully escapes his fantasy wheelhouse, see 2021’s Nightmare Alley. 7/10.

Thursday – Suspiria (2018)

Of all the art forms in the world, dance is the one I understand the least. The abstraction of the human body into a storytelling tool, the internal logic of the dancer’s decision-making versus the interpretation of the audience, the intricacies of choreography that are completely lost on the layman viewer yet still vital to the overall piece. I can appreciate dance, but I’ll never “get” it – it will always be something ever so slightly uncanny for me to consider. That’s why the dance sequences in 2018’s Suspiria were the film’s most successful element to me. Presenting the dance as something difficult, intricate, sacred, insular, even tangibly harmful and arcane. Luca Guadagnino uses dance as a weapon in this film – it’s a shame that almost nothing else on screen matches the level of pounding, vibrant intentionality. Clocking in at over an hour longer than the film it’s remaking, much of that extra runtime is dedicated to tangential plotline about an elderly psychologist investigating the school of dance, contributing to a stop-start, sluggish pace that distracts from the intensity of the dance and the surreal elements. All this extra breathing room doesn’t add as much emotional depth to the characters as you’d like, with much of the meaning becoming lost in the yawning, cavernous atmosphere. While I understand the reasoning behind the grey, washed-out pallet of the film’s world, it winds up contributing to the feeling of stagnation that haunts most of the runtime. When the film roars to life in the dance scenes, surrealist sequences and moments of violence, it’s briefly brilliant, while the story still has enough meat to keep your attention, if only it weren’t so stretched out and emotionally understated. Not bad, but disappointing. 5/10.

Saturday – Seven Samurai

Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai isn’t just one of the greatest films ever made, but one of the most fun too, eternal proof that ‘high art’ and ‘entertainment’ don’t have to be mutually exclusive. It all starts with such a simple set-up – poor villagers are tired of being pillaged each year by a gang of bandits and, unable to defend themselves, seek to hire samurai for the job. However, they don’t have the money to hire samurai, leading the village elder to simply instruct them to “find hungry samurai”. The film’s first act is dedicated to the misadventures of this village envoys as they slowly scrounge up enough starving samurai to get the job done, beginning with Kambei, an old soldier who they witness selflessly defusing a hostage situation. Kambei becomes the lynchpin of the group, strategising and organising additional members. While he is a steady and kind presence, he doesn’t help solely out of altruism – he’s also a pragmatist who knows that this is the only work left to him, accepting that the glory days of the samurai warlords are long gone and the best he can hope for is food and board, even when risking his life. Second to sign on is Gorobei, who comes aboard mostly out of curiosity. A believer in the power of chance, he’s more interested in seeing where this job will take him than in the plight of the villagers themselves. Speaking of chance, Kambei then happens to encounter an old ally, Shichiroji, who he had thought dead after their clan collapsed. Shichiroji joins simply for the pleasure of fighting alongside his old ally once more, treating the villagers like he would a conscript army as he whips them into shape for the eventual battle. As we can see, each samurai has their own reasons for helping, aside from their common need for food. Heihachi is the one character who is solely motivated by material concerns, a below-average warrior brought along mostly for his good company who is earning his keep chopping wood when the others meet him. Then there’s Kyuzo, a master swordsman who only wishes to test his skill against difficult odds and get fed while doing it. Katsushiro is the only member of the group who has completely unselfish motives – the son of a wealthy family who doesn’t at all need the peasant’s meagre offering, he joins because he believes that it’s his duty as a samurai. Of course, this naïveté puts him at odds with the others, who look down at him as a child who doesn’t understand the ways of the world. At last, there’s the seventh samurai, Kikuchiyo, who isn’t even a real samurai at all, and whose reasons for joining aren’t fully clear until late in the story. Despite being bawdy, bitter and more than a little unhinged, he is the only one who truly understands what it is to be powerless, and fights more viciously and passionately than anyone else because of this. If it seems that I’ve spent a lot of time describing these characters, it’s only to emphasise how strong the foundation of this story is – these seven vividly drawn heroes, plus the half dozen named villagers they share scenes with, create fertile ground for all manner of interactions, be they funny, tragic, angry, as these varying personalities and motivations crash up against each other and attempt to gel together in the name of their common goal, the looming threat of 50 bandits that hangs over the film’s middle act and creates the the incredible action-packed final act. This was one of the first films to shoot action scenes with multiple cameras at once, allowing Kurosawa to cut at will across the battlefield to paint the full picture of a complex, messy village-wide conflict that spans three days and barely lets up once it kicks off. A film I would easily say is a must-watch for everyone. Often imitated, never bettered. 10/10.

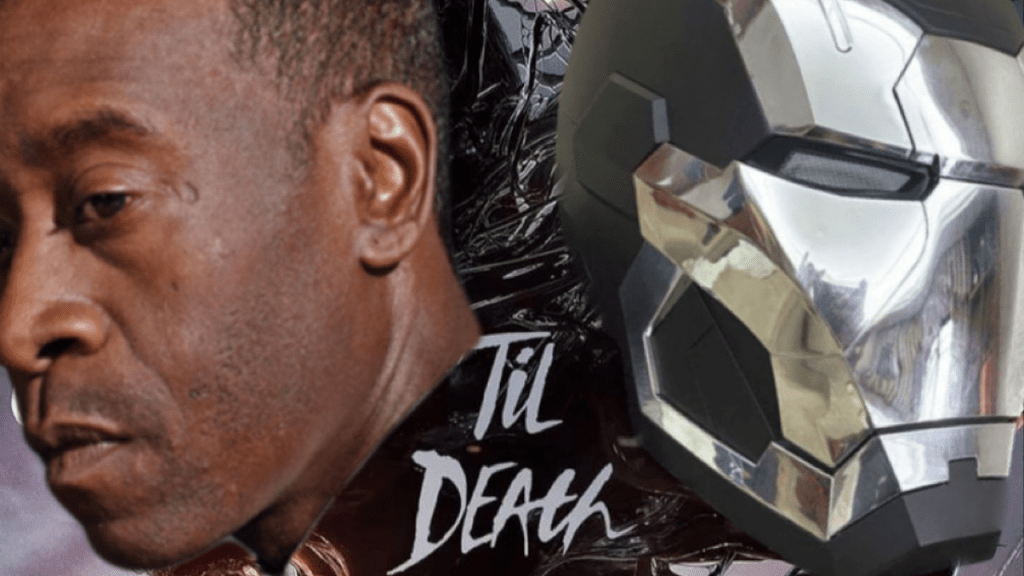

Sunday – Venom: The Last Dance

Alright Sony, pack it up – the joke’s not funny anymore. The original Venom‘s success was largely ironic and absolutely riding the wave of superhero dominance in 2018/19, and it unfortunately empowered Sony to think that people wanted more “so bad it’s good” superhero films where Spider-Man villains are reworked into solo characters. But you can’t make a fun-bad film on purpose, not really. Now here we are with a third Venom adventure where he dances to Abba, transforms into a fish and sings Space Oddity with a hippie family and none of it is half as fun as it sounds, especially because it’s surrounded by sloppy action scenes with world-ending stakes and constant cut-aways to a new cast of military characters expositing at each other in sterile sci-fi rooms. The Venom films were never entirely clear on what they wanted to be, so it’s fitting in a away that the supposed final entry would go out just as sloppy and muddled as what came before while also inexplicably laying the groundwork for more sequels. That said, I’d watch three more of these if they made them. There’s still entertainment value to be found in how many things they try, even if the central joke of Eddie and the symbiote as a bickering odd couple has worn a little thin with the retelling, and the final action sequence is surprisingly solid, especially since the effects in the rest of the film were a serious step down from the first two. Not a good movie, but a vaguely enjoyable one. 4/10.

Leave a comment