by Oscar O’Sullivan

Monday – Thunderball

To describe this film in a word – wet. Filled with visually stunning underwater sequences that I can only assume were a nightmare to pull off, the results speak for themselves – be it the ethereal beauty of exploring a downed aircraft or the gonzo insanity of the final battle, where two armies of scuba diver hack, slash and shoot at each other while real sharks circle overhead. Bond is as unflappable as ever, if not more so, utterly businesslike without any personal stake in the proceedings, free to smirk and snark his way through the adventure in that inimitable Sean Connery manner. Reality is a glimmer in the rear view mirror by now, as the cold open so deftly demonstrates by having Bond fistfight an assassin in drag before making his escape via jetpack – we are firmly in the land of make-believe, and all the better off for it. A rousing good time. 10/10.

Tuesday – Beetlejuice Beetlejuice and Nosferatu (1922)

Rarely has a film so thoroughly exceeded my expectations – from cringing and rolling my eyes at the seemingly saccharine reverence of the trailer, to smiling all the way from start to finish as I watched it on the big screen. Being free from nostalgia myself certainly helped, but I was delighted to find that this sequel was exactly as uninterested in playing the hits as I was in watching a tired retread. It’s a film that’s wonderfully alive and vibrant, tumbling from one scenario to the next with a breathless enthusiasm that makes the runtime fly by. The script has undeniable issues (no doubt a symptom of over 30 years of development), dripping with unnecessary (but enjoyable) characters and often unclear in its meaning, and while it’s visually an obvious improvement over the vapid computerised drudgery of Burton’s recent work, it could be a little sharper with the colours, more careful with the lighting. But my God, is it fun – not a single cast member lets the side down, with everyone getting more than their fair share of show-stealing gags and devastatingly dry lines. The ghost with the most remains just as rude and crude as he was in the original, with very little attempt made to sand down his sharp edges. And just like in the first film, he’s doled out in controlled doses, popping in and out for the film’s entire runtime before kicking things into overdrive and literally bending reality to take control of the sensational final act, a musical show-stopper that elaborates on the famous Banana Boat dance number without feeling in any way like a regurgitation of worn out ideas. There is also something quietly moving about the way death is used as a narrative device – it’s always sudden and undignified for the characters, leaving them forever locked in some physically embarrassing state as they wander the hallways of purgatory, but it is a relatively serene vision of life after death, with even the most threatening moments of peril and disaster in the story being handled with a light touch that keeps things from becoming any way stressful. Like Burton’s masterpiece Big Fish, Beetlejuice Beetlejuice is a story about accepting the inevitability of death, but rather than positioning it as the ultimate ending to all stories, it’s just another step in the journey. Top shelf Burton, hopefully the beginning of a return to form and not a happy accident. 8/10.

A film with an oversized legacy in pop culture, though it’s easy to see why – the titular vampire is a uniquely unnerving image in the history of the movie monster, especially impressive considering he was one of the very first efforts. Yet the film itself has, unavoidably, aged. There are certainly silent classics that retain their power, whether it be because what they present was never attempted again, or because their craft was so powerful that it’s never been topped. Nosferatu is neither – it’s influence runs deep and wide, while the story is a straight telling of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a fable repeated so often with endless twists, revisions and iterations that this achingly straightforward iteration fails to leave a mark, aside from it’s copyright dodging name-changes and uniquely animalistic take on the Count. There are moments here that justify the film’s titanic reputation, whenever it evokes a surreal atmosphere or uses complex editing to create supernatural acts. What disappoints is how few and far between those images are, with the rest of the film shot in a direct, realistic style. At the end of the day, it’s a tried-and-true horror yarn with probably the second-most iconic visualisation of the vampire (the first of course being the Bela Lugosi iteration) – I only wish it had gone further in it’s altering of Stoker’s mythos and created a more consistent visual atmosphere. 6/10.

Wednesday – Häxan

An oddity from the early days of cinema, when the boundaries of medium and genre were not yet so set in stone, Häxan is part educational documentary on the history of witchcraft and superstition, part fantastical fiction diorama of devil-worship and religious inquisitions. The two halves gel surprisingly well – imagine the fictional sequences as a recreation, the type seen in a true-crime programme. The difference here is that the film often shows us not what did happen, or even what could have happened, but what could not possibly have happened – old women flying over the rooftops on broomsticks, maidens taking the form of black cats to urinate in the house of the Lord by night, Satan prowling the streets of medieval towns and seducing women in their own marital beds. Director Benjamin Christensen makes is quite clear in his direct narration to the audience that he believes all of it is bunk and superstition, that the world of the Middle Ages simply didn’t understand science and philosophy and mental illness like the 20th Century does. What the lavish recreations of these myths serve to illustrate, in the context of revealing the “history of witchcraft”, is that the strength and omnipresence of faith in the Middle Ages made these things functionally real for people of the era – by witnessing images as they would have imagined them, perhaps we can go some way towards understanding how these beliefs drove them to commit heinous acts against their fellow man. To them, hell was as real a place as their own home. And while he often speaks as if his modern audience consists of nothing but enlightened atheists who would be far too intelligent to ever believe in such a thing as a God or Devil, Christensen expresses an awareness that the way the 20th Century treats women isn’t all that far removed from the Medieval attitudes he condemns. A timeless film, a pioneer in the now-omnipresent genre of the video essay, a visual treat and genuinely informative. 10/10.

Thursday – The Wolf Man

Surprisingly atmospheric and character-focused, this unusual entry in the Universal Horror canon trades straight-up scares for psychological drama. The Wolf Man himself barely features, lumbering through three brief scenes and making a single kill. More important than the Wolf is the Man – Larry Talbot, tortured by feelings of inadequacy as he returns from American adventures to his family home in Wales, hopelessly pining for an engaged woman, trying to reach out emotionally to a father who refuses to acknowledge his failings. It’s more tragedy than horror, an act of bravery subjecting Larry to an inescapable curse that he can’t possibly explain to anyone else. Alone and haunted by the monster inside himself, Lon Chaney Jr gives a heartbreaking performance that elevates this above a mere creature feature. The setting is suitably atmospheric, with cavernous halls, eerie mausoleums and fog-drenched forests creating a world that feels subtly “off” to enhance the ever-increasing dread that Larry is subjected to. A compressed capsule of fear and paranoia, 70 perfectly paced minutes long. 9/10.

Friday – Joker: Folie à Deux

The original Joker, for all its faults, was attempting to say something intelligent about mental health and how people are often abused and manipulated for the idle amusement of others. While the film was not especially successful in that regard, the score, visuals and performances ensured that audiences were still entertained and critics still impressed. The legacy of Joker is the entertainment, the spectacle, legions of fans who idolise the character as an icon for striking back against whoever they perceive as the enemies of society. Joker: Folie à Deux is receiving a shockingly negative response because, like the first film, it’s trying to say something intelligent – only this time, it’s succeeded, to the misery of fans everywhere. Arthur Fleck is made to stand trial for his actions in the first film – more accurately, the first film itself is on trial. Every attempt by the court to make him seem pathetic or helpless is met with outbursts and retreats into fantasy, the film ramping up the style and spectacle of the musical interludes as Arthur becomes more and more confident in his persona, egged on by Lady Gaga’s Harley Quinn, here imagined as a loony fan latching on to Joker because the shared fantasy makes her feel important and powerful. But the fantasies are just that – fantasies. Arthur is a prisoner with very little hope of freedom, his legions of supporters meaning nothing when it comes to the actual court proceedings. He is treated with a shred of decency by the guards (chief among them Brendan Gleason in top form) because they can laugh at how pathetic he is to make themselves feel better – when he lets his fame go to his head and oversteps his bounds as their personal clown, their reprisal is swift and shockingly uncomfortable to watch. In the mind of Arthur, and in the mind of many of the original film’s superfans, Joker is powerful, untouchable, beloved. But the Joker is a fantasy – when he steps out of the film’s many gorgeously constructed musical interludes and into the reality of the courtroom, he is diminished, ineffective, a pitiful performance by a guilty man digging his own grave. It’s unclear how genuine Harley’s part of the shared delusion is – her place in the plot is clearly a victim of cuts, as set videos and trailer footage show many scenes filmed that could have gone some way to explaining her elusive mental state. Is she a pure opportunist using Arthur for personal fame, or a genuine kindred spirit who believes Joker can change the world? An early scene where she daubs Arthur in his Joker makeup before having sex with him is telling – whatever her motives, she’s certainly not interested in Arthur for who he is behind the mask. The aggressively negative response to this story from the same people who venerate the original film also begs the question – did they ever care about the film’s themes, or just their own imagined vision of the character as a stand-in for their own dreams of spectacular revenge? A thorough deconstruction that manages to be fun in it’s own right without undercutting it’s message. Joker is a character who has become desperately overexposed in pop culture – with any luck, this film should close the book on him for a few years at least. 9/10.

Saturday – Phantom of the Opera and Creature from the Black Lagoon

The 1943 Phantom of the Opera films feels like an erroneous inclusion in the 8-disc Universal Monsters box-set. For one, though I will admit there is room to argue on this point, the titular Phantom is not a monster – not in the same way as Dracula or Frankenstein, at least. Unlike most interpretations of the character, he’s not even disfigured by nature, instead being splashed with acid in the film’s opening act. Even if you were to accept that his personality and actions qualify him as a monster, there is the fact that he is not the main character of the film, instead playing villainous second-fiddle (no pun intended) to the love triangle between a young singer, her policeman paramour and the male lead of the Paris Opera. Tonally, it skews closer to a Hitchcockian thriller than the gothic or sci-fi stylings of it’s ostensible contemporaries, not to mention the fact that it stands alone as the only film in this collection to be shot in colour. Why include this over, say, the 1925 version of the same tale, the original Universal Monster film? All that aside, the movie is a winner – solidly plotted with just a dash of terror to counterbalance the deft comedy of the romantic scenes, packed with lush operatic sequences that I’m not sure if I wanted more or less of and ending with a surprisingly punchy action escape capped with a perfect comedic exclamation point. Just don’t expect to be on the edge of your seat with fear. 7/10.

Creature from the Black Lagoon starts strong with a series of unique and gripping images – from an abstract conception of the creation of the universe to a primordial beach and an Amazonian expedition discovering an alarming fossilised claw protruding improbably from a cliff face. From this initial discovery we’re introduce to an intriguing cast of archetypes – the dashing young scientist and his spunky bride-to-be, the vaguely Aryan big-shot archeologist who craves success a little too much, the rambunctious but trustworthy local boat captain, etc. etc. – and are lead through a series of new settings and motives that tantalisingly tease the discovery of the creature itself, a magnificent work of makeup and costuming that looks as real today as it likely did to the audiences of the 1950s. However, and this is a real shame, that introduction to the Creature is an early climax that the film can’t quite recover from, spending the rest of it’s runtime in an increasingly repetitious pattern of attempts to capture the Creature or escape from the Lagoon leading to (admittedly impressive) underwater battles that fail to keep up the momentum that brought us to this point and, more damningly, fail to transform the solidly introduced characters into anything more that the archetypes we first meet. Never becomes outright bad, but certainly falls short of the standard it sets up for itself at the beginning. 6/10.

Sunday – Shock Corridor and Hour of the Wolf

“Whom God wishes to destroy, he first makes mad”. This opening (mis)quotation makes clear from the first frame the dramatic aspirations of Shock Corridor – this is Greek Tragedy for the modern day, man’s hubris leading him down a path of no return in a place no sane person should tread. Is intrepid journalist Johnny Barrett doomed from the start simply because his intentions are not pure? Perhaps a mind occupied with something higher than personal gain could have withstood the onslaught of insanity that we witness here. The cast of lunatics are vividly drawn, with even the background patients having visibly unique tics and manias, while the the three witnesses that Barrett has to get through to if he wants to break his big story create a simple but compelling three act structure. First is a man who believes he’s a Confederate general – really a Korean War defector who couldn’t handle the shame and ostracisation he faced on returning home a traitor. Third is a brilliant scientist who worked on atomic weapons and has regressed to the mindset of a child as the threat of global annihilation became too much for his conscience to bear. Sandwiched in the middle is the most startling, strange and compelling of the bunch – a black man who believes he is the founder of the KKK, adorned in a pillowcase hood and screaming racial obscenities for the whole ward to hear. This is Trent, the first black man to attend a college with whites, who crashed out not only because of the abuse he faced from Southern racists, but the overwhelming pressure from the media and the public to represent his entire race. Each patient is a product of their environment, driven into the sorry states we see now by perfectly ordinary societal phenomenons. So what effect will this environment of illness have on a sane man when the outside world is already perfectly capable of driving men mad? The tight script and strong performances are elevated by clean camerawork and flourishes of fantasy, including schizophrenic editing during moments of heightened fear and a standout sequence where the ward is lashed by an indoor rainstorm. Most important is the use of colour – while the film is mainly black-and-white, colour appears at three key moments when characters briefly remember the world outside, cutting away to handheld documentary footage of the Japanese countryside, tribal rituals in South America and roaring waterfalls. If colour is meant to represent sanity and the “real world” outside of the asylum walls, the fact that even scenes set outside of the hospital lack colour show that the Johnny’s efforts were futile from the start – the whole world’s already mad, just waiting for him to catch up and join it. 9/10.

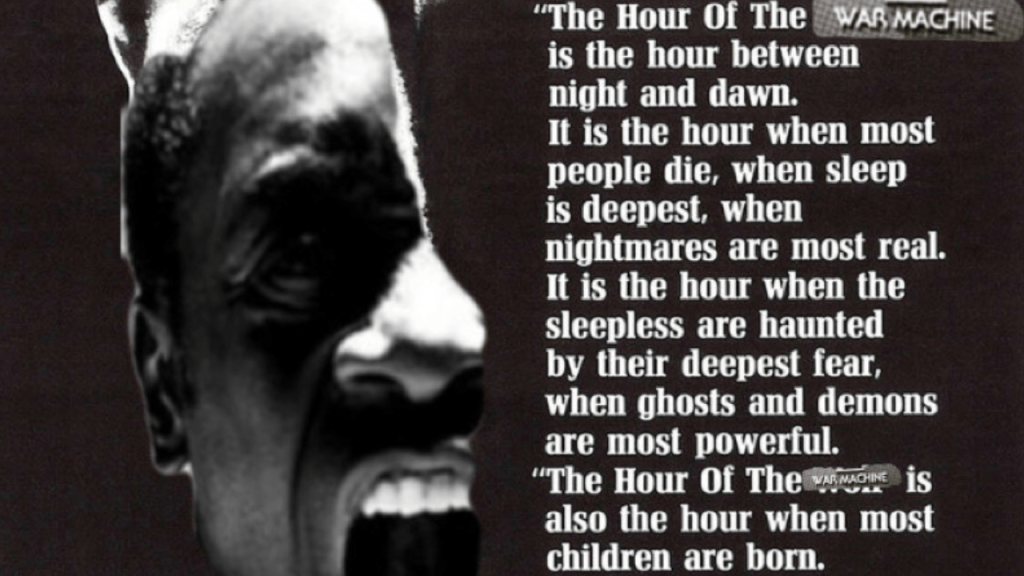

In case you haven’t noticed, I’m watching a lot of horror films at the moment. This is because it is, now sit down for this, Halloween season – or as I prefer to call it, Octoberween, a whole month set aside for horror. Previous years have seen me focus on specific slasher franchises with a couple of unique entries, but the same brand of horror over and over can get quite stale, not to mention I’ve used up the top shelf series. So this year I’ve set a programme for myself that includes a little more variety in theme, tone, language and more, while still adhering to that golden rule of horror only. Already I’ve found a gem that likely would have sat on my shelf unexamined if not for the season – Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf, a surreal and moving picture set on a remote island where an artist is tormented by imagined(?) visitors, wealthy patrons who make him feel a fraud and reopen old wounds in his marriage. Nothing is ever made explicit, not even the basics of who the couple are and why they chose to live here, but what does come to light is explanation enough without undoing the air of mystery. A particularly harrowing episode sees lead Max Von Sydow recall to his wife a violent incident that occurred while he was out fishing. Was this a real crime that haunts him, or just another nightmare? The same question can be asked of his diary entries, which oscillate between the mundane and the insane, leaving wife Liv Ullmann unsure even of her own ability to perceive the world around them. What’s clear is that she also sees the tormenters at the castle where much of the action takes place, but whether this confirms their reality or her sharing her husband’s delusion is another thing. Bergman operates with a subtle, unobtrusive eye, making even the most extreme moments feel natural and expected in that dreamlike way film often achieves – for example, a man walking up a wall and across the ceiling barely raises an eyebrow in the midst of proceedings. The use of a double framing device, where Bergman explains the real inspiration behind the film and conducts “interviews” with Ullmann in-character explaining what happened, imbues the entire film with an extra level of unease, the kernel of doubt planted in your mind compelling you to wonder, despite yourself, how much of this could have actually happened – or more pressingly, what it would feel like to believe this was happening to you. 10/10.

Leave a comment