by Oscar O’Sullivan

Monday – Blackhat

Michael Mann’s Blackhat is probably best remembered as ‘that movie where Thor is a computer hacker’, and is one of the biggest flops of the 2010s, losing about 90 million dollars at the box office and kneecapping Hemsworth’s non-Marvel career. It also put Mann in the so-called ‘Director Jail’ for nearly a decade, with last years Ferrari marking his grand comeback. In the context of when and how it was released, it’s easy to understand why Blackhat didn’t connect, but it has been reappraised and reclaimed in the years since. As a fan of Mann, I’m happy to report that it stands up as one of his best. The premise is actually fairly simple once you cut through all the jargon – Chris Hemsworth plays Hathaway, a criminal hacker released from custody to help put a stop to another hacker’s global rampage. While audiences scoffed at the idea of a computer geek who looked like Hemsworth, Michael Mann’s protagonists have always fit this mould – dangerous and brooding men of action who are also huge nerds about some obscure subject. Think of hardened bank robber De Niro in Heat studying up on rare metals, or Tom Cruise’s psycho hitman from Collateral also being a jazz aficionado – Mann understands that people are more than one thing. Hathaway explains in the film that he built up his body as part of his strategy to survive prison, both mentally and physically: “I do the time, the time doesn’t do me.” While the villain behind the cyber-attacks prefers to hide out and pay others to do his dirty work, Hathaway can operate in the physical world just as capably as the digital one, which comes in handy when hired goons are sent to his IP address or the code they need to trace the baddie has to be physically retrieved from a nuclear exclusion zone. While traditional movie hacking is often abstracted as a furious typing session or animated expression, Hemsworth is swiping phones and plugging flash drives where they’re not supposed to go, circumventing digital barriers with old-fashioned legwork. This intersection of digital space and reality is the core theme of the film, reinforced over and over again by both the story and the imagery. The very first scene has Mann visualising the interior of a computer system, becoming increasingly microscopic as we zoom into the bowels of the machine and witness the physical process of code in action, before pulling back out to witness the disastrous results of the abstract movements. As someone who is happy to believe that computers run on magic, seeing them broken down to a purely physical function is discomforting, and makes the power that these systems hold over every aspect of our lives even more terrifying than it already is. As always, Mann contrasts the real and the unreal beautifully – incredibly detailed digital images used to create a hauntingly dreamlike atmosphere, amplified by the droning, almost formless score. Blackhat is a story of alienation and dehumanisation in an increasingly digital reality, the omnipresence of technology making true safety impossible, control slipping out of the hands of governments as the very systems they use to order the world are turned against them. It’s also a story of redemption – not Hathaway the hacker coming good by using his skills for law and order, but Hathaway the man learning to feel again, grounded in his sense of self by a whirlwind romance with analyst Tang Wei and growing friendship with his rag-tag team of allies. The world isn’t made up of ones and zeroes after all – it’s made up of people, and the connections between them. 10/10.

Tuesday – Police Story 2

Sequels are always a tricky prospect. You’ve can’t just repeat yourself beat for beat, but you’ve also got to avoid deviating too far from what people enjoyed in the first place. Police Story 2 manages to keep the spirit of the original mostly intact, but buried somewhat by a thriller plotline that shoots off in too many different directions and winds up breaking up the action too much. Officer Chan is back again, suspended for his OTT antics at the climax of the first film but roped back into action after a bomb threat at a mall reveals a blackmail conspiracy. Rather than reacting to the moves of the criminals, Jackie is more proactive this time, assembling a colourful but under-developed task force to investigate the case through undercover stings, stake-outs and surveillance. It’s solid police procedural stuff, but overstays its welcome as the means to an end – more explosive Jackie Chan action. Nothing in this film quite lives up to the insanity of the original, but Chan is always a delight to watch in action, and the hand-to-hand fight scenes especially shine. 7/10.

Wednesday – Public Enemies, Police Story 3: Supercop and The Big Heat

To be clear I am not entirely insane and jobless – Public Enemies was a late-night Tuesday watch that spilled over into the following day. I only watched two movies in full during Wednesday itself, which is a perfectly reasonable amount on a day off thank you very much.

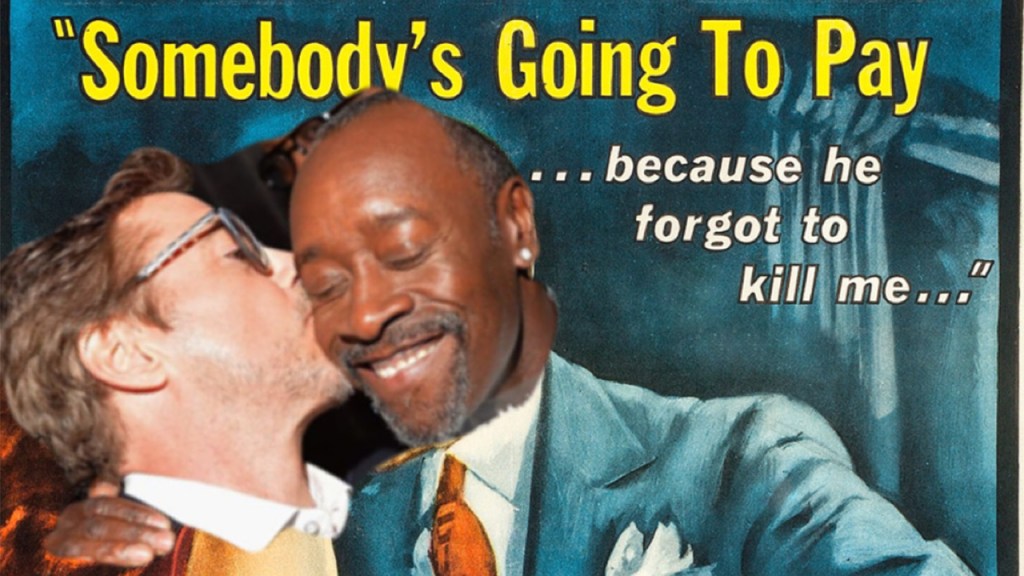

Public Enemies enemies is, conceptually, a slam dunk – Michael Mann tells the true story of John Dillinger, the last great American outlaw, as he is frozen out by the increasingly corporate criminal world and hunted down by the newly formed FBI and it’s modern methods of surveillance. Dillinger is more akin to a celebrity than a criminal, flirting with hostages and drawing crowds of cheering fans when he’s arrested. He sees himself as a modern-day Robin Hood, champion of the people, and his fame is exactly what makes him the top priority for the FBI – a high-profile super-crook they can take down to cement their public credibility. J. Edgar Hoover sends his best man, agent Melvin Purvis, played by Christian Bale. Purvis is a serious, maybe even dull man, but he has an unassuming charm that makes him the perfect public face for the FBI. He’s also quick to recognise that intelligence alone won’t be enough to take down Dillinger and his ilk, bringing in a squad of old-school lawmen to co-ordinate a militaristic take-down after their initial arrest attempts are scuppered. While Purvis gets disappointingly little focus in the plot, his arc is still just about there in the background – growing disillusioned as he realises his work hasn’t created a more peaceful world, just one where state violence is more ruthlessly efficient. Johnny Depp as Dillinger gets the better end of the deal, with his motivations more adequately examined. Depp is solid in the role, one of the last he filmed before his substance abuse and personal issues started to upend his career, much more easygoing and charming than the usual Mann protagonist, all his hardness and pain buried deep. If Mann’s crime films could be seen as an ongoing charting of the evolution of law and order, then Dillinger represents a time when crime could be treated as something casual, even fun – the advent of technological surveillance and the consolidation of criminal groups into corporation-like bodies drove the men like Dillinger to extinction, creating a world where only the truly focused and hard-hearted can operate on their own terms. The broad scope and thematic depth of the film within Mann’s own body of work make it one I love to discuss, but unfortunately not one that I especially relish watching – if anything it casts it net too wide, capturing too many ideas and moments without honing in on a core story or emotional journey. It’s certainly exciting, with some of the most dynamic gun-fights and chases Mann has ever captured, but it ultimately leaves me cold. The visual style is also something I can’t fully wrap my head around – while the rest of Mann’s digital works take place in the modern day, seeing the 1930s recreated in the visual language of the 21st Century remains disorienting, though obviously striking. Despite it’s strengths, the overly sprawling story and failure to dredge up any deeper feeling lets down what could have been a true-crime masterpiece. 7/10.

After the so-so second film, Police Story 3: Supercop is a return to form that doesn’t quite match the gonzo magnificence of the original but does bring it’s own unique strengths to the table. Leaving behind the cops-and-robbers structure that weighed down the previous film, Officer Chan is going international this time, signing on for a top secret mission to infiltrate a cartel in mainland China and nab the big boss who’s flooding Hong Kong with drugs. The change in scenery is welcome after being confined to samey industrial locations for the last two films. This is like a whirlwind tour, cramming in as many locales as possible – pristine military training centres, open-air prison camps in middle of lush rural landscapes, a quaint little village with a filthy, bustling wet market, a James Bond-style private island lair and a tropical paramilitary compound that gets blown to smithereens in an explosive assault. This makes the previous entries look positively peaceful with the amount of gunplay and major battle sequences. Luckily for Officer Chan, he’s got some backup on his undercover mission – Oscar-winner Michelle Yeoh as a no-nonsense Chinese army official who matches Jackie blow-for-blow in the stunt department. The plot is a lot of fun and keeps shaking things up to avoid repeating itself, with the ‘undercover agent’ aspect being played equally for laughs and drama. The undeniable highlight has to be the finale, a car chase through jammed city streets that escalates into a helicopter escape and a final kung-fu battle atop a moving train. Jackie dangles from a chopper in flight and Michelle Yeoh performs a legendary motorcycle stunt – this is what action cinema is all about. 8/10.

The Big Heat is a cop drama with an unusual twist – the cop is actually a good guy. I don’t mean that in a snide ACAB fuck the police kind of way – the majority of cop movies, even the ones sympathetic to the police, will have their hero be troubled in some way. He could be overly violent, emotionally numb, crooked, corrupt, scared, unfaithful – tortured cops make for good drama. But our hero here is an anomaly, a man seemingly free of any vice or trauma that gets in the way of his job. Sgt. Bannion is a pillar of virtue, entirely incorruptible and dedicated to seeing justice done, no matter who he has to piss off to do it. He’s also a dedicated family man, with the film dedicating considerable time to his humble but loving home life. The plot kicks off when he refuses to back away from his investigation into the death of a prominent officer. Suspecting foul play in the supposed suicide, he badgers the man’s widow and discovers he was having an affair with a call girl. When said girl turns up dead on the side of the road, Bannion is told in no uncertain terms to drop it, but his conscience won’t let him. The audience is then let in on a secret – not only are the cops all bought and paid for a ‘respectable’ crime kingpin, everyone knows it and nobody dares to step out of line. Bannion’s insistence on following the thread puts him in serious danger, but he’s tired of standing by while everyone else ignores justice to save their own skins. What follows is difficult to watch at times, a good man having his life destroyed for doing the right thing, his obsession with bringing down the system of corruption becoming more and more of a personal vendetta. It’s a film that’s violent without being gory, with Bannion more likely to beat a crook senseless than gun him down, and chief bruiser Vince Stone knocks around his girls in some rather nasty scenes of domestic abuse – the focus is squarely on the aftermath of violence and the mental effect it has on both the survivors and the perpetrators. Director Fritz Lang was one of the great masters of silent cinema, and his background in visual storytelling serves him well here, especially in the set design. The locations aren’t quite expressionistic, but they’re certainly evocative, each backdrop having it’s own readily apparent mood that reflects the conflict of each scene. The bar where Bannion first attempts to get answers is made somewhat ominous by the amount of empty space it projects around the patrons, as Bannion is isolated and unwelcome in this place. His home is cramped but cozy, a haven of warm domestic bliss – when he is later forced to move out, we see it stark and empty, a reflection of the growing hollowness in his heart. It’s a very cold and angry film that is held back a little by the strict codes of 1950s Hollywood, but it still gets away with a lot in terms of themes and content, and turns the mandated happy ending into something that feels more ambiguous. 8/10.

Thursday – The Master

Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master is a film that I still find difficult to penetrate on the fourth go round. On each watch another aspect becomes clear, another angle reveals itself, but the full picture never resolves, can never resolve, because that is the point – there are no answers. Joaquin Phoenix plays WWII veteran Freddie Quell who can’t seem to readjust to civilian life and finds himself accidentally joining the inner circle of a New Age pseudoscientific cult. Freddie initially scoffs at the idea of ‘past-life hypnosis’ as just another useless therapy like the PTSD treatments he received in the military, but is drawn in my the magnificent charisma of the cult’s Master Lancaster Dodd, played by the late great Philip Seymour Hoffman. As the cult is hounded across America by doubters, haters and the long arm of the law, Freddie’s fierce loyalty becomes dangerous, leading him to beat critics of the cause senseless and draw down even more heat. It’s Lancaster’s wife who first realises that Freddie isn’t necessarily loyal to the cause or to the ideas – he is loyal to Lancaster Dodd the man, the only friend he’s ever had outside of the military. The film hints and suggests all along that Mrs Dodd is the real brains of the operation – while Lancaster originates the ideas and genuinely believes in his method, his wife is the one who sees their potential as a tool of control, and is more worried about the cult’s image and profits than seriously proving the truth of it’s methods. She’s played with expert restraint by Amy Adams, switching between the soft, reassuring mother figure and the frigid baroness as her plans call for it. Freddie is given the ultimatum of committing fully to ‘processing’ or leaving forever. We see an extended montage of Freddie banging his head against this brick wall of psychotherapy, his frustration only growing as he realises the promised magical fix isn’t going to come, until he convinces himself that the programme has worked and he is now a fully functional member of society. The angle I found myself latching onto this time around was the entire story as a metaphor for addiction. Freddie is a ‘functional’ alcoholic, a hardcore drinker that brews his own potion from liquor, engine fuel and whatever else he can get his hands on. It’s clear that pre-cult, his addiction is slowly killing him – he’s aggressive, anti-social, frequently passing out at inopportune times and gradually slipping into an isolated transient lifestyle. The cult is initially an avenue for him to indulge his addiction in a safe environment – Lancaster is charmed by his erratic behaviour and more than happy to drink with him. Their initial ‘informal processing’ works for Freddie because the drink has lowered his inhibitions and because he’s connecting with Lancaster as a person, not with the formula of the therapy. When he is later forced by the cult to quit drinking and take part in regimented processing, he flounders. The programme is meant to help participants connect to their past lives, but Freddie only feels that he is losing himself, as if his drinking is a part of of his personality and he may not recognise the person left behind when all the rest has been drained out. He powers through because he believes in his friend Lancaster, and he believes that the final answer of how he can fix himself is coming – when the big revelation of the cult’s second book is revealed to be a meaningless re-wording of past ideas, the facade falls apart entirely. Lancaster knows the new work is pathetic – with the implication his wife forced him to go down this route for the sake of their image – and his dejected bitterness is barely masked by his ‘unflappable leader’ act. Neither him nor Freddie got what they wanted, and they part ways as two lonely, unfulfilled men who know deep down that they have failed each other in the pursuit of something that can never be reached. Even if the plot is too impenetrable or heavy for you, the visual and musical beauty of the film is undeniable, one of the most vibrant looking films ever produced with an evocative score by Johnny Greenwood. Like all of Paul Thomas Anderson’s films, this is a widely-beloved work that still somehow feels underrated. 10/10.

Friday – Fancy Dance

Even the most ardent Emma Stone fans should be able to admit that Lily Gladstone should have won the Oscar for last year. Not even in terms of the strength of the performance – always a subjective argument at best – but in terms of what it means for their respective careers, which should be recognised as the true value of the Academy Award. A Best Actor or Actress win is a feather in the cap for an established performer, but could be life-changing for someone early in their career. Killers of the Flower Moon was an incredible breakout role for Gladstone, and hopefully it’s success will be enough to propel her on to further success, but an Oscar win would have surely solidified her spot in Hollywood. I am now going to say something that may alarm you – we are all morally obligated to watch every movie she appears in. Hollywood needs to know that we want to see Lily Gladstone in more movies. Fancy Dance was technically produced before Killers of the Flower Moon, but was only released recently on Apple TV. It’s a solid family drama about a woman forced to look after her niece when the girl’s mother vanishes, struggling to find answers when the feds refuse to take the disappearance seriously and battling to keep custody of the girl when Child Protective Services take issue with her criminal record. Gladstone is excellent in the lead role, an independent no-nonsense hardass who makes her living from grifts and petty theft, teaching her niece how to fend for herself but always being there for her too, a badass with a soft heart deep down. Road trip movies are always a fun ride, and the best of this story takes place during the journey to the titular fancy dance. The pair steal gas by swapping the nozzles on pumps, dodge nosy immigration cops and sleep in empty show houses. The mystery of the missing mother is a foregone conclusion, which makes the regular cutaways to the investigation feel a little unnecessary – why not give us more time with the two leads on the run or with the bumbling but well-meaning grandparents trying to take custody of the girl. Fancy Dance does nothing exceptional as a film, but it’s a touching story with a fascinating cultural angle and I’ll always be seated for Lily Gladstone. 7/10.

Sunday – Zatoichi at Large

Not good!

The first Zatoichi film I’ve genuinely disliked – one dud out of twenty-three is a phenomenal hit-rate. Let’s rapid-fire this son of a bitch – the plot is a charmless rehash of several prior films, almost nothing worthwhile happens for over half of the runtime, the supporting cast are deeply annoying, Zatoichi himself has no arc or lesson to learn, the whole film is very mean-spirited and doesn’t earn the emotional pay-offs it tries to trot out later, the colour palette is dull as dishwater until the very final scene suddenly does something visually striking, the editing feels rushed and slapped together with scenes ending randomly and the score cutting off at odd times, and there’s only one major action sequence right at the end that, while entertaining in it’s scale and bloodiness, doesn’t do anything the series hasn’t done before. It pains me to rate a Zatoichi film so low, but this just wasn’t it. 3/10, here’s hoping the last handful of adventures are a little more refined.

Leave a comment