By Oscar O’Sullivan

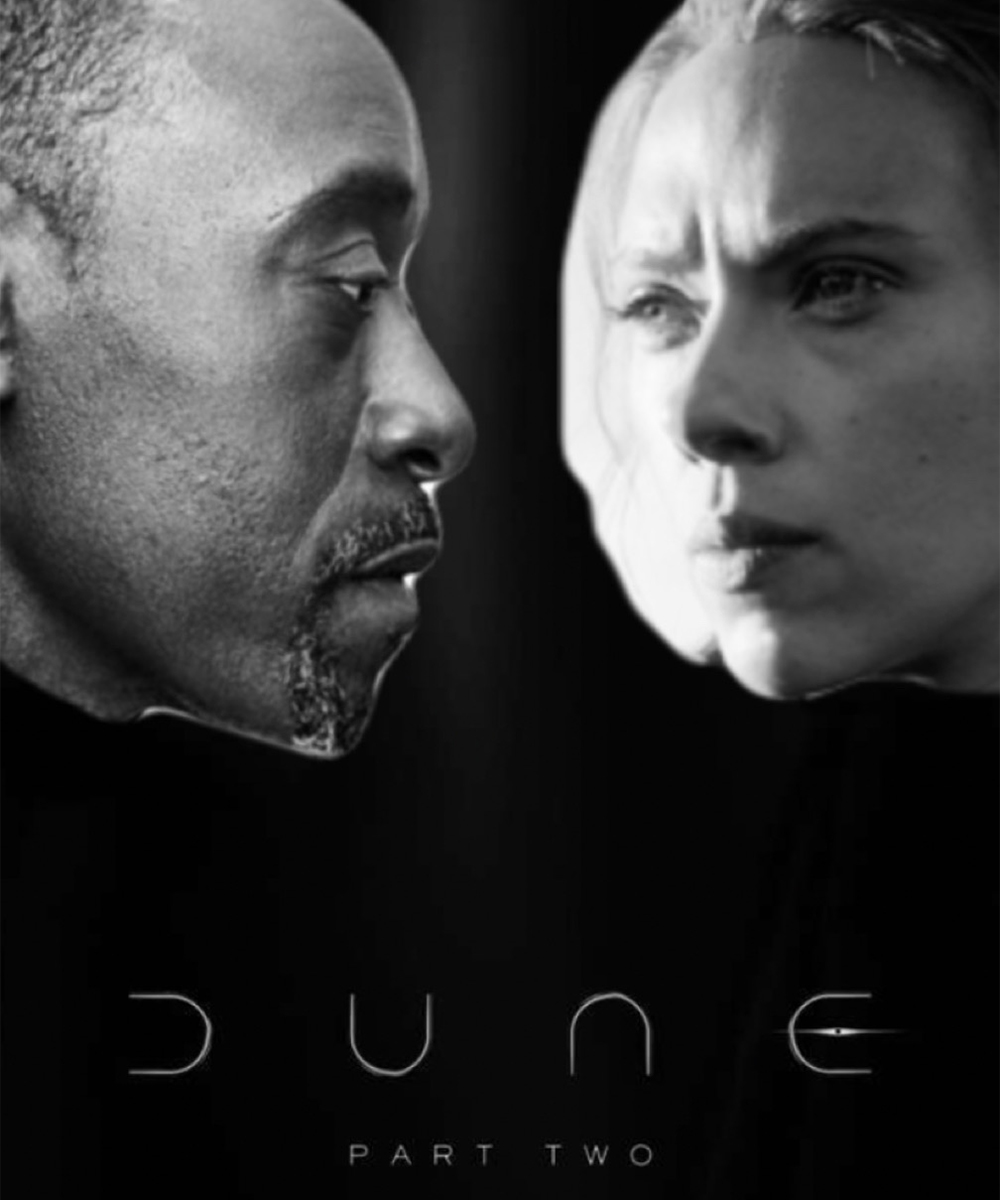

Monday – Dune Part Two

I started off my week the right way with a third round of Dune Part Two. I think it’s safe to assume that everyone reading this is at least aware of this film and it’s predecessor, so I’ll skip the explanations and get right into it. While there are some films that can only impart their full impact the first time you watch them (perhaps because of a shocking moment or twist that loses power once seen), I’m a firm believer in the power of the rewatch. Seeing Dune 2 for the third time, issues I felt on my first watch continue to fall away into irrelevance. The slow first hour flies by with foreknowledge of the larger structure, and eyebrow-raising character decisions are suddenly crystal clear.

The character and performance I’ve found myself the most entranced by is Javier Bardem’s Stillgar. After essentially appearing as a cameo in Part One, playing a stern and inscrutable Fremen leader, the casting of an Academy Award winner in this tiny part has paid off in the sequel, where Stillgar is both comic relief and the central pillar holding up the main theme of the story. Stillgar’s belief in Paul and in the prophecy is played humorously throughout the film, with his regular interjections of “as it is written” and awed reactions to Paul’s every action getting big laughs every time I see the film. But as Paul’s legend and his influence over Fremen society grows, Stillgar’s faith becomes dehumanising, uncomfortable. His professions of belief become wild-eyed and manic, his subservience to Paul so pathetic that he is willing to die for no reason other than it would advance Paul’s journey. Bardem’s performance begins broad and jovial, cracking jokes with Paul in a delightfully throwaway manner, and narrows in scope as the character’s agency falls away, until he is nothing more than a symbol, an object to be used by his Messiah. As Paul laments, “these were once friends, now they’re followers”.

On the other side of the coin, a character whose depth and agency has been hugely enhanced by this adaptation is Chani. In the source material, Chani is a love interest in the classic mold, a pretty, uncomplicated object for the hero to pursue and win and eventually angst over. The first film seems to set up this same path with Chani’s limited screentime. She appears almost entirely in brief visions, whispering sweet nothings to Paul, ethereal and enticing, dressed in flowing white robes with her hair down and the light of the setting sun illuminating her from behind, beckoning him down his path into the desert. It’s the perfume commercial version of femininity, and the casting of Zendaya, fashionable it-girl, was chuckled at as a mercenary move by the studio, a focus-grouped play to draw in the youth audience. It almost flies under the radar that, when Chani appears in the flesh at the end of the first film, she immediately destroys that idealised image that Paul (and the audience) has built up. She is sour, suspicious, squinting side-eyed at this stranger who acts overly familiar, a warrior first and foremost. This subversion is continued and expanded upon in Part 2, tranforming Chani from love interest to deuteragonist. Book Chani is just as much a blind believer as the rest of her people, but here she is part of a vocally secular group in their society, questioning the need for a Messiah in the first place, and giving voice to subtext that the book failed to properly communicate. She is the first Fremen to welcome Paul as a person rather than a prophet, and it’s her respect and eventual love that grounds Paul and makes him reconsider his plans to weaponise the prophecy, to try and fulfil his revenge as an equal to the Fremen instead of a ruler. Zendaya’s performance is revelatory. I’ll admit that I didn’t hold her in high regard as an actor going in, but this is the first role I’ve seen that really let her prove herself. She is subtle, stoic, convincingly bashful and giggly during the love scenes and chillingly venomous in her exchanges with Jessica. It’s an internal performance, conveyed through reaction and expression rather than long-winded, award-clip-ready monologues, and her almost entirely silent presence in the final act has completely sold me on Zendaya as a serious performer. This may be me talking out of my ass, but it struck me as an almost genderless role in this incarnation. There is nothing in her function or performance that reads as explicitly, traditionally “feminine”, especially compared to how she was presented in the visions of Part 1. She is an equal partner in the relationship with Paul, his superior in many ways, more knowledgable and confident. Her motivations carry none of the traditional signifiers of the “female character”, her cultural values take priority over her relationship with the male lead, her conflict with the other female lead is politically rather than emotionally driven, and she is ultimately the one person in the story who does not fall in line with Paul’s leadership, granting her more dignity and agency than any other character.

If you haven’t seen this movie yet, what are you doing? I shouldn’t even have to tell you to get yourself to the cinema. An unqualified 10/10, must-see movie of the year so far.

Tuesday – Dune Part Two

Monday night’s trip to Arrakis was such a great time that I got up on Tuesday morning and went again, this time to the Arc Cinema. While there’s definitely an advantage to having the massive MAXX screen at Omniplex, the Hypersense screens at the Arc provide stunningly crisp visuals. Projection has become a real problem in cinemas today, dirty screens and poorly tuned projectors giving films an unfortunate hazy feeling and burned-out speakers crunching audio, but my experience with the Arc screens since it reopened in December has been incredibly positive, with visuals comparable to a high-definition TV screen, and rock-solid sound quality. Hopefully this standard is maintained as the equipment ages.

It feels like Denis Villeneuve and cinematographer Greig Fraser took to heart the criticisms of visual sameness that the first film suffered from. From the stunning high-contrast orange hue of the opening, it’s immediately clear that this instalment will be a different beast visually. The cramped interiors of the underground Fremen hideouts are presented in muted browns and greys, in contrast with the vast golden dunes of the planet’s surface presented in sweeping vistas. The Imperial homeworld is ethereal, with loving close-ups of cultivated plant-life and airy, ornate architecture. Giedi Prime, site of the extended introduction to Feyd-Rautha, is a truly alien location. Unlike traditional black-and-white photography, which can be converted to colour after the fact if needed, Dune 2 filmed these scenes with infrared lenses, fully committing to the aesthetic. The results are immediately recognisable as something unique, milky white standing out bizarrely against stark greys, creating a world that feels entirely artificial and industrial. During a pivotal scene, Paul envisions a future where Arrakis’ sands give way to a churning ocean, and the effect of this sudden wall of cool blue is so striking that every time I see it, it feels like the temperature in the room has dipped a few degrees.

At the risk of repeating myself, Dune 2 needs to be seen to be believed. Visuals like this were meant to be seen on the big screen, with sound that shakes the floor and burns every note of the score into your memory. Catch it in a large format before some shit like Ghostbusters takes over those screens. 10/10, movie of the year.

Wednesday – I Am Cuba (Soy Cuba)

Labelling something as a “propaganda film” is some heavy baggage to lay down for a viewer, even in cases where the film very much is, from intention to execution propaganda. I Am Cuba was created as a collaboration between the USSR and the freshly-Communist Cuba in the early 1960s, and is essentially an educational picture. In four standalone segments it covers the impacts of capitalist and colonial oppression on the people of Cuba, and the journey of those who fought back and carried out Castro’s revolution. What I found most interesting was the way the film blurred the line between nationalist and ideological propaganda. The crew behind the film, helmed by director Mikhail Kalatozov, were predominantly Russian, financed by the Soviet Union. As expected then, it is full of traditional Stalinist imagery; crowds of workers marching in unison, farmers brandishing tools like weapons, spirited proclamations of the glory of Lenin’s writings. What adds a unique element is the way the film focuses on Cuban culture too, portraying it as a vibrant and beautiful nation, and each segment of the film focuses on the struggle of an individual as representative of the larger whole. While playing up cultural pride and using hero figures isn’t exactly uncommon in Soviet Cinema (epics like Ivan the Terrible transplanted Soviet ideals onto medieval Russian history before this), it is an ideological mismatch. Communism is supposed to be above old vices like national pride and individualism, and the use of them as tools for propaganda feels like an admission of failure to sell the ideals of Communism on their own merits.

The question is, does knowing that a film is propaganda rob it of it’s power? Not necessarily. It can be easy to forget that the historical propaganda films that we learn about in schools never disguised their intentions. The audience always knew they were being sold a message, and watching a film like I Am Cuba from a modern perspective doesn’t necessarily make us more enlightened or critical than audiences at the time would have been. This film was unpopular in it’s home country for perceived infantilisation of the Cuban people, and unpopular in Russia for being insufficiently Communist. The only reason it is discussed today is because it was rediscovered in the 1990s by American filmmakers, who were blown away by the technical innovations it contained. This is the real power of cinema as a tool of propaganda. By creating value outside of it’s ideological intentions, through visual craft, storytelling, music, strength of performances, propaganda films live on in discussion of film, and they can’t be discussed without confronting the ideas they contain. Even the most objectionable, overtly hateful films will be passionately defended by seemingly rational people on the grounds of artistic merit. That does not mean that these people have fallen for the propaganda, but they are a part of it. By recommending this film, I am recommending Soviet propaganda. Not because I believe in it, but because I believe it’s worth confronting. Study of overt propaganda can help us to discover the hidden propaganda of other films. For example, every American war film ever made needs to be viewed through the lens of military propaganda, no matter how innocuous they may seem. There is no such thing as an apolitical film. I Am Cuba gets an 8/10 from me, and a qualified recommendation. It’s not an easy movie to see, unlikely to come to any streaming service, and rarely played in cinemas (the screening I attended was politically motivated and we’ll leave it at that). It does have an upcoming physical release, but it’s actually available for free on YouTube too. Only for those who are really interested.

Friday – The Count (1916)

Charlie Chaplin, an icon so ubiquitous in pop culture that many people could recognise his Little Tramp character on sight without ever actually having seen one of his films. This early example is my first full watch of a Chaplin movie, and it’s got me wanting more. It’s simple but layered with brilliant acting touches, heavily orchestrated physicality in service of a breathless onslaught of gags both big and small. Chaplin is a delight, impish and playful, casually violent in a manner not usually seen outside of Tom and Jerry, a Bugs Bunny-esque underdog who always takes control of the situation to get one over on his bigger, tougher opponents. The Count (and probably all of Chaplins short films) is on YouTube, it’s twenty minutes long, and there’s basically no reason not to check it out next time you’re scrolling for something to watch with your dinner.

Saturday – The Last Waltz and The Aviator

The first of today’s double bill is one I don’t have a whole lot to say about. The Last Waltz is a documentary concert film by Martin Scorsese that captures the final live performance of The Band in 1976. Breaking up the concert footage is interviews Scorsese recorded with members of the group about their time together. The performances are fantastic, even as someone with no familiarity with the group or their music the concert atmosphere is infectious, and there’s almost more celebrity guest performers than songs by the group alone. The interview segments might be more meaningful to someone who has followed The Band and it’s members, but this isn’t a movie that sets out to teach you anything about them. It’s a hangout movie, tunes and good times and banter with the boys. It’s on Amazon Prime right now, so give it a go if you’re a fan of country music.

I also watched Scorsese’s The Aviator, starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Howard Hughes. This was the second movie in the long run of Scorsese-DiCaprio collaborations, and the first one to really feel like an award-bait play. Old Hollywood setting, all-star cast playing historical figures, emphasis on period visuals and production design, it’s very much the stereotypical “Oscar Bait” formula. This isn’t to say that’s a bad thing, but it does lend something of a calculated, artificial feeling to the film if you let it distract. Scorsese still does a brilliant job of keying into what makes the Howard Hughes story interesting, an exceptional man using his unlimited wealth and privilege to pursue his own passions and drive technology forward, whose perfectionism is more like a mania that gradually impacts his ability to function as a human being. It’s a demanding role that Leo rises to with his usual brand of dynamic, always-on, look-at-me acting. If young DiCaprio had been any less naturally talented, his earnestness would be irritating, but he makes it work, even if it is too much at times. His performance here never quite reaches the level of complete believably, largely because the craft of his acting is constantly visible. The contrast between Leo’s work and a more natural, laid-back performance can be seen in his dialogues with Alec Baldwin. Now I’m not saying Baldwin is in any way a better actor than DiCaprio, but he’s acting on a completely different wavelength here. He’s casual, confident, completely at ease, there’s still effort and craft at work but it’s disguised by Baldwin’s natural winking charm. I needn’t even mention that Cate Blanchett gives the real standout performance of the picture (they did give her an Oscar for it after all). Her first scene as Kate Hepburn is almost alarming, playing like a parody of an old-timey fast-talking go-getter, but the mannerisms become natural as the character becomes more comfortable with Hughes, and the line between Blanchett’s performance and the layers of in-universe performance Hepburn uses to protect herself become inextricable.

The Aviator is a fascinating movie that feels like it could have taken the material further, that doesn’t say as much as it could about the wider ideas that Hughes represents, choosing instead to focus on the personal struggles of a sick man with the cultural context as simply a (very beautiful) backdrop. Funnily enough, it feels like a blueprint for Oppenheimer, and those similarities (and the strange production history connecting them) might be something I examine in a separate piece. A weaker entry in the Scorsese canon, but still a rock-solid 7/10. It’s not streaming anywhere, but if it does pop up, I’d say give it a shot.

Sunday – Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold

For the last few weeks, I’ve had a very easy time picking what I’m going to watch on a Sunday. Let me introduce you to Zatoichi, the blind swordsman. Played by Shintaro Katsu, Zatoichi was the lead of twenty-five films between the years 1962 and 1973, and I’ve made it my mission this year to work my way through them all. The basic premise of the franchise holds true across all the films. Zatoichi is a blind man who wanders from town to town working as a masseur, and also a blindingly fast sword-fighter. Everywhere he goes, he is harassed by Yakuza gangs who want his help in petty wars, struggles to keep his hands clean, and usually breaks the heart of some local girl he has to leave behind when he moves on to the next adventure. The first five films follow this formula quite faithfully, so Chest of Gold was something of a breath of fresh air. Zatoichi is usually a neutral figure who just wants to indulge in the simple pleasures of life, and the scenarios he finds himself in are morally ambiguous, forced to choose which pack of thieves to side with to protect some innocent caught up in things. In this instalment, Zatoichi is cast in a more classically heroic role. Accused by villagers of helping to steal their tax money, he sets out to clear his name and save their livelihoods, coming into conflict with bandits and dirty administrators, and ultimately proving more noble and altruistic than we’ve ever seen him before. To counteract this new moral purity, the violence is more sustained and graphic than before. Where Zatoichi once would have dispatched opponents in an instant with bloodless slashes, now there are bursts of blood and opponents writhing in agony, innocent villagers tortured onscreen, and the first villain to give Zatoichi a serious battering in their climactic showdown. It seems that quite a few of the early Zatoichi movies are currently available on YouTube (I have the complete boxset but can’t recommend picking that up unless you’ve got some spare change handy), and they’re pretty much all worth watching if you’re a fan of samurai action. There’s some light continuity between entries, but each one is functionally standalone, so take your pick. Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold is the best instalment yet, and maybe the best place to start aside from the original, with the caveat that it’s visuals will make the prior films seem tame by comparison. A 9/10.

Leave a comment